Many parents teared up at the UCR School of Medicine’s second White Coat Ceremony in 2014, but one in particular stood out to Meera Nair, PhD, an associate professor of biomedical sciences. Her first lab technician, Josiah Chung, MD, had come to work with her to gain more experience before applying to the UCR School of Medicine, his first-choice school—and now he was starting his journey to become a doctor with his family proudly looking on.

“His mother was crying, thanking me for taking a chance on him,” Nair recalled. “That was really moving to me to make a difference in that person's life, and to have recruited an awesome student who's now a physician doing wonderful things.”

Nair, who earned her PhD at the University of Edinburgh in the United Kingdom, moved to the East Coast to conduct postdoctoral research at the University of Pennsylvania followed by the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation in New York. “I like solving problems that have impacts,” she said. “At every step, I try to make my work have benefits that go beyond myself or the research community.”

She originally came to UCR because of its plans to open a medical school. The day Nair was hired, in October 2012, the SOM received its preliminary accreditation. “To me, it was really exciting to join the biomedical sciences faculty, which had this motivated mission to serve the community, to have a new medical school, and to contribute in that way,” Nair said.

The role was a perfect fit for her because of her love of teaching medical students while working on research projects that both benefit the community and add to the collective scientific knowledge about COVID-19 and other conditions. “I’m giving students the basic biomedical knowledge to be effective physicians, and at the same time doing research in that field to make an impact,” Nair explained. “So it's a two-fold thing that really satisfies my academic and career endeavors, and my life endeavors, and I feel very passionate about that.”

Training future physicians

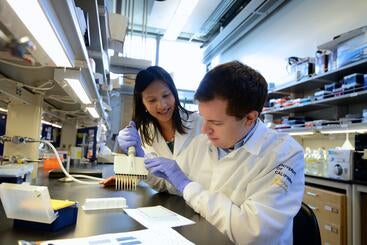

Nair is particularly drawn to working with students like Chung who have faced challenges in their pursuit of medicine. Chung, who majored in microbiology and immunology at UCLA, worked in Nair’s lab during a gap year while applying to medical school. “Being from the Inland Empire, attending medical school at UCR was a wonderful opportunity to pursue my dream of becoming a physician in my own community,” Chung recalled. “When I was accepted into the UCR School of Medicine, Dr. Nair was ecstatic and incredibly supportive of my future career goals.”

“I really believe strongly in the pipeline program, so I think what's really important is that we really look at the journey and how far they’ve come,” Nair said. “One on one guidance is important to get them to where they are now, and it's so rewarding to see that they're successful.” In her time at UCR, she has trained 5 undergraduates from UCR and around Southern California who subsequently entered the SOM and became physicians.

Nair works with current medical students and residents at UCR as well.

One former student, Luqman Nasouf, MD, worked in Nair’s lab during the summer after his first year of medical school and is now a pulmonary and critical care fellow at UC Irvine. “Dr. Nair had a drastic impact on my career and how I continue to learn to this day,” he said. “Dr. Nair provided a structure to my scientific evaluation of medical literature, taught me appreciation for scientific method, and helped me become more thorough and thoughtful in my approach to learning.” He continued sepsis research with Nair as an internal medicine resident at UCR, ultimately co-authoring a paper with her in the Journal of inflammation Research in 2022.

The paper was the second clinical collaboration Nair published at UCR. “It was really helpful to be local and do clinical research, and to work with students from the Inland Empire so they're involved in their own community,” she said. “We were really doing research that served our community and the people who suffered from these diseases that have no cure.”

Nair also gives back to UCR by helping with admissions. “We really try to find people who fit our mission, and also understand that some of them might have faced a lot of hardships,” she said. “It's the only way that you realize what's going on, and it makes me even more motivated to help the students because I read their admissions and the people that we admit are simply resilient and amazing.”

Connecting to the community

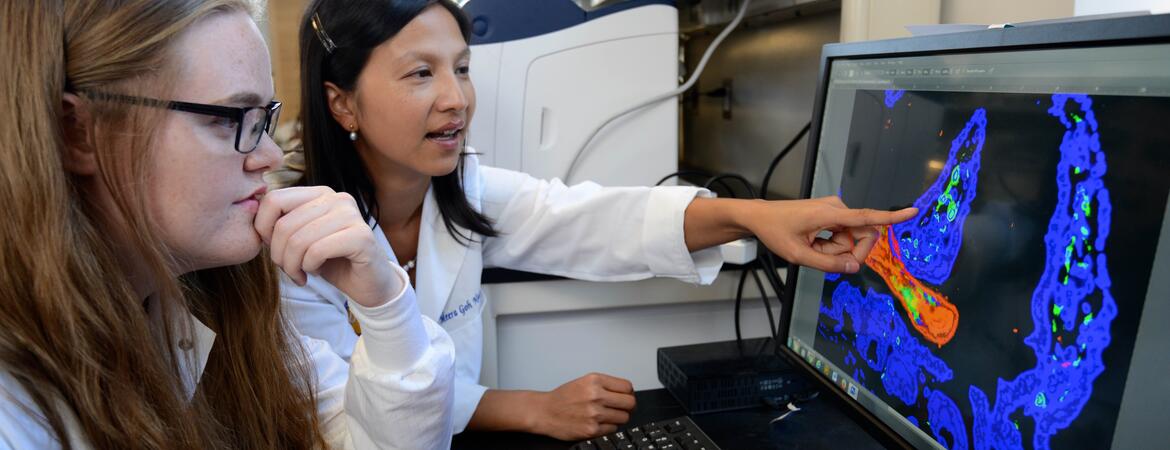

The other primary part of Nair’s role revolves around research. Her curiosity and interest in problem solving as a student led her to focus on immunology, a field that became central to the community during the COVID-19 pandemic.

When the pandemic hit, Nair recalled, “we really didn't know what was going on; as scientists, we were as clueless as everybody.” UCR’s position as a community-based school made it possible to do unique research to learn more about the new virus.

Nair worked with the SOM’s Center for Health Disparities Research and the Department of Social Medicine, Population, and Public Health (SMPPH) to conduct community-based participatory research. This included visiting the homes of people in the community to receive consent for their research participation—a task that normally would fall to graduate students but for the risks of COVID-19. “We were in uncharted territory, collecting specimens to sequence the virus and understand how the virus was changing,” Nair said. “It was a scary time, but it was memorable hearing participants’ individual stories about how excited they were about the medical school, and that they really wanted to participate in research because it was such an unknown area.”

Since then, Nair has helped further the school’s connection to the community by hosting community events, such as a COVID-19 community chat held in April 2023.

“It wasn't only doing the research that was important, it was important to communicate the research to the participants who enrolled in our study,” Nair explained. “That's exactly the mission of our school.” She added that it’s critical to create a dialogue and build trust with stakeholders, who can also help shape the direction of future research.

Contributing through research

Nair’s research focuses on how differences in people, such as various medical conditions, affects their immune response. This is particularly important in the Inland Empire, where there’s a high prevalence of chronic conditions. According to the Prevention Institute, heart disease and stroke, cancer, respiratory conditions, and diabetes are responsible for 63% of deaths in Riverside County.

“The immune response is there to combat infection, but there are so many other factors in a person that can make that immune response better or worse,” Nair said. “That’s why that diversity of the immune response is so important to understand so we can have more targeted methods to give therapies to specific people.”

Nair said that the pandemic highlighted the importance of diverse immune responses after different people experienced varied outcomes from the virus. Determining the appropriate immune response to target the infection in different people was Nair’s challenge, as she pointed out that triggering the wrong immune response could be worse than getting no immune response at all. “I like the analogy of, there's a burglar in the house, and you could arrest him without damaging the house, or you could just bomb the whole house and the burglar as well—but you'd have no more house,” Nair said. “So you need a balanced response.”

Her research has focused on immune responses to infection for decades, but it has expanded to include COVID-19 as well as inflammation in general. “I think one of the impacts that I've had is really highlighting the complexity of the immune response and how it's different in different people,” Nair said.

A biomedical sciences family

Nair said that UCR is a great place for her because of its community focus and its supportive biomedical sciences department. “I view our faculty as family and we really respect and help each other, so it's a really collaborative sort of environment that has helped me thrive,” she said. “I'm not in a silo here and I love that.”

With the upcoming 50th anniversary of biomedical sciences at UCR, Nair said the department still retains its family feeling. “We've expanded on doing research on health disparities that we didn't have when I was here 10 years ago, we're recruiting faculty, and we also are still expanding in terms of our NIH funding, which is increasing,” she said. “We're using innovative tools to address unanswered questions in the field of biomedical sciences, but we still maintain the family feel that I think is more rare in other institutions.”

Nair added that beyond biomedical sciences research, the department has expanded its role to helping train physicians in the School of Medicine. “I would say the most important part is how resilient and what a forward trajectory our biomedical sciences department has followed, from just biomedical sciences to now a medical school as well and growing community research,” she said. “I think that trajectory is the most important one we've seen in 50 years, and biomedical research is now putting UCR on the map.”