The UCR School of Medicine will add a new master of public health (MPH) degree program in fall 2024, adding to its efforts to improve health among the people of Inland Southern California.

The two-year program integrates public health expertise from across UCR’s campus, resulting in an in-depth focus on local to global public health problems and solutions. Ultimately, it aims to train a new generation of public health leaders committed to increasing health equity in the Inland Empire.

The MPH program will begin with around 15 students and plans to expand each year. It is seeking students who both want to understand health inequities at the community level, and to partner with communities to develop and implement effective public health initiatives.

Why a new MPH program?

A team of experienced and dedicated public health leaders came together to build the new degree program at UCR.

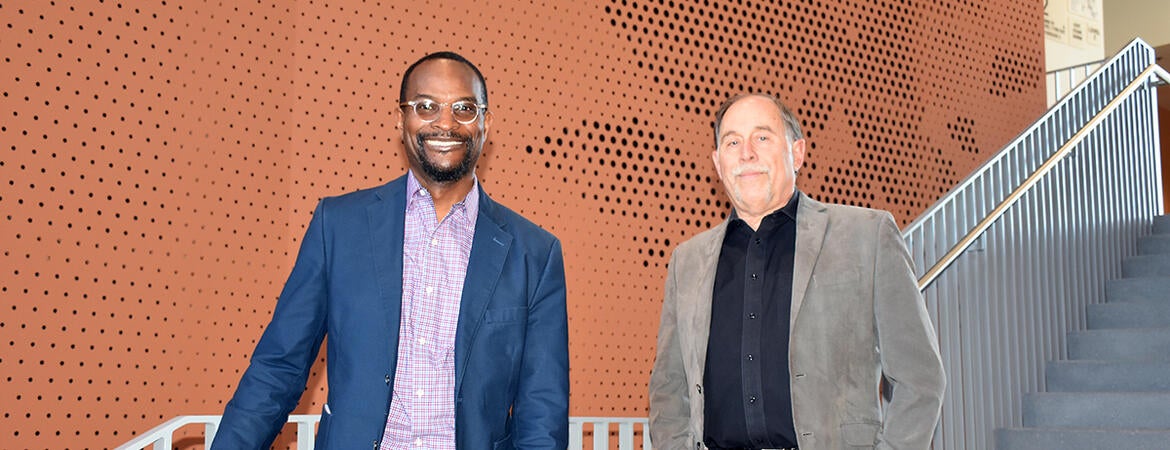

Mark Wolfson, PhD, the William R. Johnson Jr. and S. Sue Johnson Endowed Chair in the Department of Social Medicine, Population and Public Health (SMPPH), joined UCR in fall 2019 with the new MPH program as one of his goals.

“There are quite a few MPH and even doctoral programs in Southern California, but the vast majority of them are clustered along the coast,” said Wolfson, who began working to develop the new program in early 2020. “There are only a handful that really have their eye on Inland Southern California, so we thought there was a real need, but also a real opportunity for UCR because of our focus on health equity, social mobility, and community engagement.”

Mario Sims, PhD, a professor of social medicine, population and public health at UCR, was also drawn to the university in part to spearhead the MPH program. After working with the community-based cohort study Jackson Heart Study for 20 years, Sims wanted to build something new while contributing to health in Southern California, where he grew up. With these goals in mind, and a career focused on investigating health disparities, he joined the UCR School of Medicine in 2022 and immediately began contributing to the program.

“There's an interest in understanding health equity here in the Inland Southern California region, but there's not been a driving program for research and teaching that's been a part of this region like there needs to be,” said Sims, who was recently appointed as the MPH faculty program director. “Training the next generation of public health and population health scholars in this area is very important, and UCR is well suited to do it by adding an MPH program to its catalog.”

The program has also been championed by Deborah Deas, MD, MPH, the vice chancellor for health sciences and the Mark and Pam Rubin dean of the School of Medicine. “The MPH program will draw on the School of Medicine’s strength in engaging the community,” she said. “It will create a collaborative approach to study and address social determinants of health while training public health professionals who are dedicated to serving the Inland Empire.”

A unique degree

The development team collaborated with local public health leaders, including the Riverside County Public Health Department, to create a robust curriculum for the community-focused degree program.

The program’s concentration, health equity, addresses the heart of the issue in the medically underserved region. “We're focused on equity right out of the gate,” said Wolfson. “That cuts across all of our offerings, it’s baked into the curriculum, and we think that's really important--especially for serving our area.”

The program also includes interdepartmental faculty currently representing 17 departments across five colleges at UCR: the College of Natural and Agricultural Sciences (CNAS), the School of Public Policy (SPP), the College of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences (CHASS), the Marlan and Rosemary Bourns College of Engineering (BCOE), and of course, the School of Medicine (SOM).

“It's a real strength, the way we've been able to draw on the resources and expertise from all across campus,” Wolfson said. “That's not something you necessarily see at other schools, where it's much more contained.” Faculty members may teach courses, serve as thesis advisors, guest lecture, and more.

“The faculty involved in the MPH program are the most inspiring people I’ve met during my time at UCR,” said Moazzum Bajwa, MD, an assistant clinical professor and director of the Longitudinal Ambulatory Care Experience (LACE) Program who contributed his public health expertise to the development of the MPH program. “They represent several disciplines across UCR and each of them leads transformative community-based research and programs in the Inland Empire.”

Through the SOM’s LACE Program, all medical students already receive training in public health as well as work directly with patients in the community. Still, Bajwa wholeheartedly supported a standalone MPH program.

“One of the key public health lessons highlighted by the COVID pandemic is that health disparities disproportionately affect low-income communities as a result of generations of structural violence,” Bajwa explained. “We need to develop and maintain experts in public health who intimately understand the needs of our Inland Empire communities, and the MPH program is one of several pathways to do that.”

He continued, “I chose to work at UCR School of Medicine precisely because of that emphasis on community-based research and advocacy, and I’m confident the MPH program will expand on that in a meaningful way.”

Joining a new generation of public health scholars

UCR faculty anticipate that the program will help the community while offering a promising career path for graduates. “I think there is a growing realization of underinvestment nationwide in the public health infrastructure, so it’s a growing field,” said Wolfson. He added that the team developed the program with input from potential employers, such as the health department. “I think it'll help people build their careers and ultimately have a positive impact on the health of the population of Inland Southern California and the reduction in disparities,” he said.

Sims concluded by pointing out that it’s up to those in the local area to address local issues. “I think that's important for us to realize--nobody's going to do it except those of us who are here,” he said. It’s important to unify efforts under an MPH program, Sims continued, to “understand what's going on and how we can be a part of the solution rather than continually ignoring the problem or operating in a piecemeal way.”

“Hopefully this will produce scholars and practitioners who are sensitive to the role of community in formulating strategies for improving health and achieving health equity,” Sims added. “The goal is to train a generation of scholars who may be members of the communities but who will also engage our community in efforts to improve health.”