For Jason Hasegawa, class of 2025, being the first on the scene of a medical crisis or inserting an emergency chest tube was just another day in his roles as a first responder and, later, an army medic. Completing his first UC Davis undergraduate course, algebra 1, however, terrified him.

“I didn't believe in myself academically. A few weeks before that, I was just an infantry medic, and then here I was at college,” Hasegawa recalled. “It was so hard, because I didn't know that people like us could do that,” he added, explaining that most of his army friends hadn’t gone to college either.

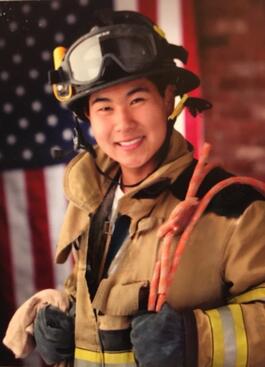

Hasegawa’s father dropped out of high school before later earning a master’s degree, and growing up Hasegawa didn’t plan to attend college at all. After nearly losing his mother to pregnancy complications when he was 7, Hasegawa dreamed only of becoming a firefighter like the ones who saved her life. After a few years as a firefighter and emergency medical technician, though, his interest in austere medical care led him to join the ski patrol and then the army.

As the only combat medic responsible for 50 infantrymen, Hasegawa developed close bonds with his fellow soldiers in the Army National Guard. They supported him when he decided to start college, taping his organic chemistry flashcards to their backs on training marches to help Hasegawa study and not letting him stand guard so he could sleep. “These patients weren't just patients, they were my best friends,” Hasegawa said. “So I had this crazy idea of wanting to just achieve the highest level of training possible so I could bring these guys home.” That goal took him to medical school.

Veterans Healing Veterans

When Hasegawa started at the UCR School of Medicine in 2020, he realized he couldn’t be the only veteran qualified for medical school. However, he said that combat medics he spoke to were interested in becoming physicians, but, like his younger self, didn’t think it was possible. “When you see people like yourself, and they're doing things that you couldn't even dream of doing, it becomes a little more realistic. You start thinking hey, maybe I can do that too,” he said.

Hasegawa’s first-year roommate and fellow veteran Jeremy Santiago, class of 2024, agreed about the difficulty of attending medical school—but added that the military gave him the mindset to succeed. “When you're in undergrad, people talk about how difficult medical school is. And I think the military really taught me, "What does difficult mean?” Santiago said. “Is it impossible or just hard? So I think the military really gave me that mindset that this too shall pass.”

The two decided to do something to help their fellow veterans. During their first year at the SOM, they started a student interest group called Veterans Healing Veterans to support veterans attending and considering medical school.

For Santiago, the group has three goals: to increase the number of veterans in medical school, support veterans on campus and in the community, and help other medical providers better understand and treat veterans.

Increasing the number of veterans in the School of Medicine began with knowing their number in the first place, a statistic that hadn’t previously been tracked. They recommended that the admissions staff add a checkbox for veterans to application materials and discovered that only a few veterans were enrolled in each year of medical school at UCR. While the veteran population of Riverside County was the eighth-largest in the U.S. in 2020, veterans were severely underrepresented among UCR SOM students.

The disparities reinforced the group’s second goal of supporting veterans both in and out of medical school. While implementation was challenging, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic when Hasegawa and Santiago founded the group, they worked to build a mentorship program for veterans applying for and attending medical school. This effort included helping veterans understand the process as well as ways to effectively apply their skills to be admitted and thrive in school.

The limited number of veteran medical students and veteran doctors led to the group’s third goal: helping non-veteran medical providers and doctors in training understand this population to help improve their care. Santiago noted the long delays often present in the Veterans Affairs healthcare system and veterans’ frustration with accessing treatment. Familiarizing doctors in training and current providers with barriers veterans face, he said, may help improve the care they provide.

“Maybe one of my classmates 10 years from now will be working at the VA and see a veteran patient who has no trust in their care, has no trust in the service, is cursing at them and pissed off,” Santiago explained. “Maybe by understanding these shortcomings of the system, they will be able to see why that veteran’s this way and how they can still impact their care with what they have, rather than writing this guy off.”

Support from veterans on campus

The pair also worked with other veterans on campus, like UCR Veteran Services Coordinator Tami Thacker, who arranged a meeting between the group, Veterans Affairs Secretary Denis McDonough, and Congressman Mark Takano in 2021.

"The impact these prospective doctors make on our current veteran community shows hope for the future," said Thacker. "They are helping to educate not just our UCR undergraduates who aspire to become doctors, but also helping to heal the sick and injured in the community. Seeing them graduate gives me hope that others will follow in their paths."

Scott D. Pegan, PhD, a professor of biomedical sciences and a lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army, worked with the group as well.

As a veteran, Pegan personally faced some of the struggles the group was created to ease. After completing basic training, for instance, he wasn’t aware that he was eligible for financial aid for college and said no one told him what steps to take. With the Veterans Healing Veterans group at the SOM, “If we find that you're a veteran, we want to make sure that you know what all your options are,” he said. “It doesn't mean we're going push you into those options, we just want to make sure you know that these are all things that can really help you on your path to where you want to go.”

Pegan added that bringing more veterans to medical school doesn’t just allow UCR’s student population to better represent the surrounding community, but helps the SOM live up to its mission of increasing diversity.

“The goal is to provide a diverse set of physicians from a diverse set of backgrounds to tackle the challenges in the Inland Empire, and I really see this as kind of an unmet need that the School of Medicine hasn't been able to fully realize yet,” he said.

From fatigues to scrubs

For Santiago and Hasegawa, veterans’ potential to make unique contributions is another essential reason to support their journey to medical school.

“Someone who’s been in the military has so many experiences and traits that are applicable to medicine,” Santiago said, listing resilience, determination, and the ability to work under pressure as a few examples. “There are lots of good things that people don't realize they learned by being in the military. Fatigues and tanks don't seem to apply to scrubs--but we have to figure out how they do.”

Hasegawa added that veterans contribute technical training and life experience as doctors, but that most importantly they bring the ability to work with diverse teams. In the military, “you get people that are from all different walks of life, different socioeconomic statuses, and from all different corners of the country and even the globe,” he said. “There are going to be issues, but we work past that because if we don't, none of us go home.” This mindset, he added, “is something that I think would make a medical school class even stronger.”

As they prepare to graduate, Hasegawa and Santiago have passed the Veterans Healing Veterans group down to the next generation of veteran medical students--Anthony Sarmiento, Jesus Iracheta, and Diana Ortiz--to continue their mission. Santiago said he still mentors veterans who are interested in attending medical school, and both remain passionate about helping more veterans become doctors and serving veterans themselves.

Hasegawa plans to return to the army and said he's leaning toward specializing in trauma surgery. “It’s incredible to be a medic for the toughest people I know,” he said. He hopes to stand up for his patients like he did for one infantryman early in his army days, when he went against orders to keep the injured soldier from training at the risk of Hasegawa’s own career. “I learned that if I can't fight for myself, I can't fight for others,” Hasegawa said. “I need to get the most education I can so I can fight for people.”